The Aran Islands, Viking Theatre Dublin

The Red Curtain Review, January 2016

The Aran Islands has a remoteness that perhaps today is not as noticeable, aided by the hotels, B&Bs, ferries or small planes that bring the visiting tourists there daily. When J.M. Synge visited the islands more than a hundred years ago, he noted that to the locals the interest of most people living outside the islands seemed to be the study of the Gaelic language, rather than perhaps the majority of visitors today.

Joe O’Byrne’s adaptation brings us to the islands on Synge’s first boat trip, the ebb and flow of the water prominent against the fishing and nautical set, alongside some wood and turf cuttings and a sole, wooden chest with a piece of paper and a pen on it, reminding us that we are seeing

everything through the eyes of a writer, something the play itself doesn’t let us forget. Synge’s interest, which is outlined in the programme notes on his life, are somewhat more personal. Synge, best known perhaps for The Playboy of The Western World, took inspiration from Yeats who was

enthusiastic about the Irish renaissance and urged him to live on the islands and ‘express a life that has never found expression’. Synge did just that and over four years spent part of each year on the islands, living as they did, and documenting the stories, the funerals, the evictions, and lives of the islanders, some of which are brought to life

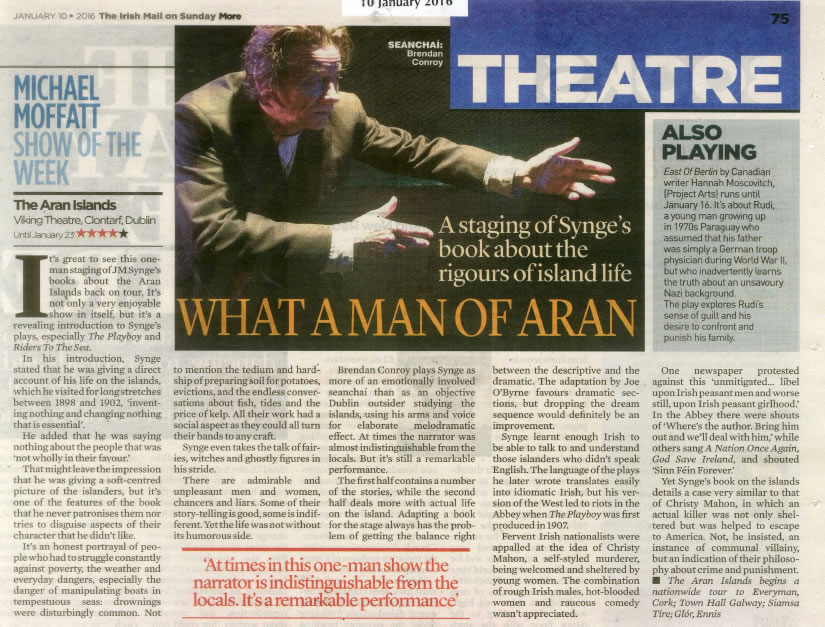

on stage effectively, but with the observer’s eyes and words. Brendan Conroy gives life to Synge, dressed as an islander, the scuffed

and worn toes of the leather shoes adding a roughness to the costume that is far from upper-class writer. It is an excellent performance, given

that it is over two acts, and Conroy is the sole performer, although some of the island characters do come over as being similar. His voice

and body enact the ups and downs of the sea, in at times a very earnest, even highly dramatic performance, tempered by the quieter,

more intimate moments; Joe O’Byrne’s lighting design being Conroy’s best aid, working in unison with the actor creating the scenes, with

some images difficult to forget even after the performance has long ended.

The programme notes do tell us of the importance of Synge’s writing about the Aran Islands, creating a social document, and of course, it is not so easy to adapt a social document to the stage. It could be more selective rather than be very faithful as it seems to be, or even use some of the intriguing back story as part of the narrative. There is an

earthiness to it, but some more reflection might yield more results. O’Byrne has visible love for this piece, adapting, directing and lighting it, and it is easy to see why. Any writing that charts a way of life, especially one now gone, is intriguing, a reason travel writing can be so curious especially those written many years ago and read in the present.

Bringing this to the stage can only be a good thing, although a little trimming might be the touch that reels us in completely.